Ergonomics is the study of how workers and the work environment interact. It is a broad-based approach to OHS that considers how the design of work affects the human body and its health. Ideally, ergonomics starts with job design. Job design comprises the decisions employers make about what tasks will be performed by workers and how that work will be performed.

Job design includes establishing the physical dimensions of work. This includes the size and location of the workspace, and what furniture, tools, and equipment will be used, as well as the temperature or lighting of the workspace. Job design also determines the nature of the tasks, including their complexity, pace, and duration and how individual tasks and jobs relate to one another. Finally, job design often includes making decisions and assumptions about the characteristics of the workers who will perform the work, including their height, weight, sex, and other physical and mental abilities.

The decisions made during job design can have significant effects on workers’ health and safety. Poor work design has negative effects on worker health. For example, if you have ever worked at a job where, at the end of the day, your eyes hurt (due to poor lighting) or your back was sore (because of standing on a cement floor), you have experienced ill health caused by poor ergonomics.

A core principle of ergonomics is “fit the job to the worker, not the worker to the job.” More specifically, ergonomics seeks to ensure that the design of work matches the anatomical, physiological, and psychological needs of the worker. Yet some ergonomic hazards are easier to “see” than others. For example, back pain from heavy lifting is easier to identify than fatigue to due poor shift rotation design. The broad acceptance of lifting as hazardous and requiring control shows that the relationship between the hazard and the injury is both direct and well accepted. By contrast, there are many factors contributing to worker fatigue. This makes it difficult to definitively prove that shift rotation is an important factor in worker fatigue.

The aspects of ergonomics that have been more readily adopted are the design of tools, equipment, and workspaces. For example, we have seen an increase in more appropriately designed keyboards, work stations, retail scanners, and other equipment. There has also been greater attention paid to minimizing manual lifting and handling of loads. Buildings are being built with better climate and air-quality control.

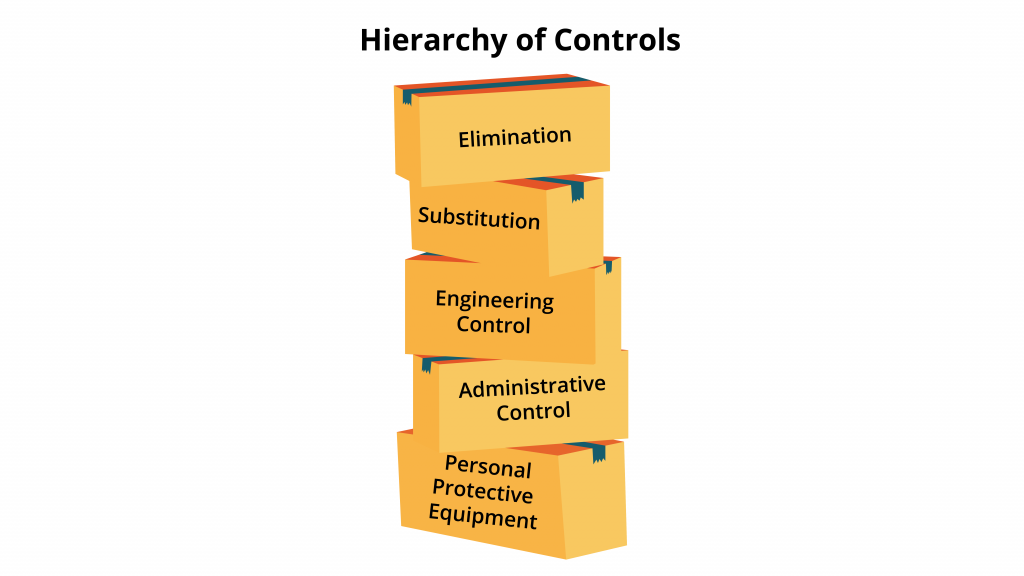

Employers have been more reluctant to address other ergonomic issues because the required changes affect the work process or may impede management’s ability to direct work. For example, providing a better-designed chair to prevent spinal deterioration is easier and cheaper than altering the work flow to reduce the mechanical forces exerted on workers’ spines by twisting to reach objects. This reluctance to address some ergonomic hazards echoes employers’ preference for PPE over engineering and administrative changes that we saw in Chapter 3. As well, government OHS regulations tend to address only small pockets of ergonomics, such as manual lifting, while remaining silent on many other aspects.

A common health effect of poor ergonomic design is repetitive strain injury (RSI). As we saw in Chapter 1, RSIs (which are sometimes called cumulative trauma disorders) are injuries to muscles, nerves, tendons, or bones caused by repetitive movement, forceful exertions and overuse, vibration, and sustained or awkward positions. RSIs frequently occur in the hands, wrists, and arms but can also afflict legs and other key joints. Carpal tunnel syndrome, frozen shoulder, trigger finger, tendonitis, bursitis, and (more recently) Blackberry thumb are all examples of RSIs.

Any task that requires either the same movement over and over again or puts the body in an awkward position can lead to RSIs, especially if repeated over a long period of time. RSIs have only gained acceptance as the outcome of workplace hazards over the past 20 years. They were first acknowledged in factories with workers on assembly lines. Even today workers in some occupations, such as retail clerks, typists, and restaurant servers (notably occupations dominated by women), still have greater difficulty having RSI claims accepted. Among the reasons for the slow acceptance of RSIs is the murky causality of the disease: did you get it from keyboarding at work or playing squash on your own time? RSIs may also worsen even after the hazardous tasks are eliminated and can appear as a result of work not normally associated with repetition. There has been inadequate epidemiological research into the full range of factors that lead to RSIs.Helliwell, P., & Taylor, W. (2004). Repetitive strain injury. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 80, 438–443.

Meat-processing and cashier jobs are both associated with the development of RSIs. Meat-processing is a difficult job that involves heavy, dirty, and repetitive work. “Workers must repeat the same motions again and again throughout their shift. Making the same knife cut 10,000 times a day or lifting the same weight every few seconds can cause serious injuries to a person’s back, shoulders, or hands. Aside from a 15-minute rest break or two and a brief lunch, the work is unrelenting.”Schlosser, E. (2001). The chain never stops. Mother Jones, 26(4). http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2001/07/dangerous-meatpacking-jobs-eric-schlosser Cold temperatures (most of the work is performed in coolers to delay deterioration of the meat) compound the risk of injury. One study found that meatpacking workers are up to 80 times more likely to experience RSIs than other workers.Piedrahita, H., Punnett, L., & Shahnavaz, H. (2004). Musculoskeletal symptoms in cold exposed and non-cold exposed workers. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 34(4), 271–278.

In the past 20 years, RSIs have become widely acknowledged as a serious OHS issue in meat-processing plants. Facing significant economic pressure, meat processers have kept the speed of the production line high. They have also gotten rid of unions and shifted their hiring to more vulnerable immigrants and migrant workers. In short, employers have not controlled the hazards—they have just made it harder for workers to assert their safety rights. Not surprisingly, meat-processing workers frequently have difficulty having their RSIs accepted as “real” injuries and the hazards posed by the work process controlled.

Stories of Repetitive Strain Injuries

Ana Ramos came from El Salvador and went to work at the same IBP plant as Albertina Rios, trimming hair from the meat with scissors. Her fingers began to lock up; her hands began to swell; she developed shoulder problems from carrying 30- to 60-pound boxes. She recalls going to see the company doctor and describing the pain, only to be told the problem was in her mind. She would leave the appointments crying. In January 1999, Ramos had three operations on the same day—one on her shoulder, another on her elbow, another on her hand. A week later, the doctor sent her back to work.Schlosser, E. (2001). The chain never stops.

Being a grocery clerk—moving small items across a scanner and bagging them—may not seem like physically demanding work. Over the course of a shift, however, a clerk can be required to lift more than 2000 kg of groceries. The lifting is in thousands of swipes of mostly small packages. The repetition, combined with twisting and awkward positioning as well as standing for long periods, make grocery clerks highly susceptible to RSIs.

Mary Ann Anderson has been a cashier at a grocery in Queens for about 12 years. With a remodeling about two years ago, the store replaced old-style cash registers with price scanners at the checkout stands. That’s when Anderson’s pain began. She noticed the scanner made her do more pulling, lifting and twisting of her wrist—she held each item at an angle so the scanner could read the price code. Also, Anderson and others found that taller clerks handled the raised weight scales and register tapes better than shorter clerks, but the shorter clerks were more comfortable with the scanner height. And nothing was adjustable. Last year the tendinitis in Anderson’s arms and wrists forced her to miss more than two months’ work.Cummins, H. J. (1992, January 26). Scanners add up injuries for grocery checkout clerks. Seattle Times. http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19920126&slug=1472135

The part-time, gendered nature of retail work has made it more difficult to get retail-related RSIs recognized. Employers are reluctant to make substantial design changes to checkout stalls, as they are designed for consumer, rather than worker, convenience. It is easier to replace the workers when they “wear out.”

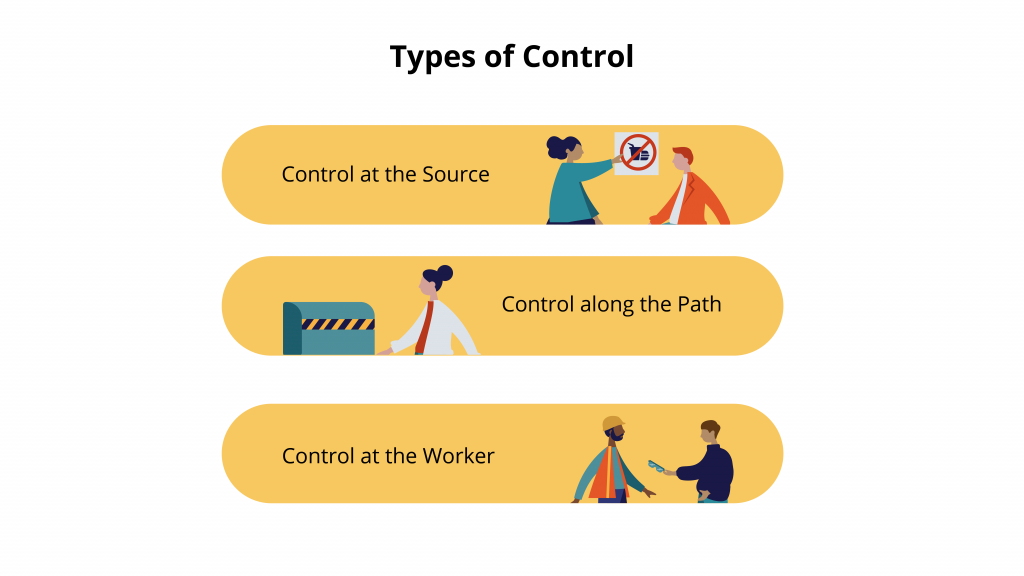

Engineering controls are the best way to address ergonomic hazards. Wrist supports, rest breaks, and other controls-at-the-worker fail to address the root cause of the hazard and do not effectively prevent the onset of injury. Ergonomic principles require that the design of the work be altered to better fit the needs of the workers in question. What those specific controls look like is highly dependent upon the nature of the work and the demographics of the worker.